Ride the Tram

In just 12 minutes, the Aerial Tram glides skyward 4,139 vertical feet. The summit offers staggering 360-degree views of the Tetons, Jackson Hole Valley, and surrounding mountain ranges. The "Top of the World" provides amazing access to a plethora of great hiking and running trails, climbing and the occasional snowball fight. Oh, and don't forget the world-famous gourmet waffles in Corbet's Cabin.

Save by purchasing in advance. Same-day online tickets match window rates.

Valid for one day Aerial Tram use. Also includes same day Evening Gondola, Bridger & Sweetwater Gondola sightseeing (June 6 - Sept 12, 2026)

Included in your sightseeing ticket

1 Sightseeing trip via the Aerial Tram

1 Sightseeing trip via both the Bridger & Sweetwater Gondolas (June 6 - Sept 12, 2026)

1 Evening Gondola trip, providing access to The Deck & Piste Mountain Bistro (June 6 - Sept 12, 2026)

360-degree views of the Tetons

Access to high-alpine hikes

10% off food at Tram Dock

10% off logo wear at Teton Village Sports, JH Sports, Hoback Sports, the Resort Store and the General Store

*All Tram and gondola rides must be used on the same day. Sightseeing tickets are valid for one day only.

Pricing Starting At

$49

$54

/ Person

| Advanced Online Rate Starting at | Window Rate | |

| Adult Sightseeing Ticket | $49 | $54 |

| Junior Sightseeing Ticket | $32 | $35 |

| Senior Sightseeing Ticket | $39 | $43 |

| Family Pass (up to 2 adults & 4 juniors) | $120 | $120 |

The above prices are online only and window rates are higher. Save by purchasing in advance. Same-day online tickets match window rates. Rates vary per season. June 6 - Sept 12, 2026, Bridger and Sweetwater Gondola access is included with your Summer Sightseeing Ticket, including one Evening Gondola trip (in addition to the Aerial Tram). Teewinot chairlift access is not included with this ticket and is reserved for Bike Park bikers only. This sightseeing ticket does not include bike park access.

Winter Sightseeing

Ride our Aerial Tram 4,139 ft to the summit of Rendezvous Mountain and take in the breathtaking beauty of winter in the Tetons. Sightseeing is available for purchase in person, weather permitting. Tickets are $55 per person.

Please call 888-DEEP-SNO for availability & more information.

From The Blog

Grand Teton Skywalk

Soak in the views on the all-new Grand Teton Skywalk viewing platform at the top of Rendezvous Mountain! The Grand Teton Skywalk is accessible via a sightseeing ticket on the Aerial Tram.

Best Sightseeing in Jackson Hole

Jackson Hole is blessed with some of the country's most beautiful views. While simply walking around the valley will conjure feelings of amazement and wonder, visiting the high alpine spots on this list will leave you genuinely awestruck.

Top 5 Hikes in Jackson Hole

As a resort nestled within Bridger-Teton National Forest, right on the border of Grand Teton National Park, we are blessed with a beautiful alpine environment. This rugged mountain terrain provides stunning vistas and a wide range of trails for hikers of all abilities.

Wyoming's Wild Side

Wyoming is a wild place! I'm not referring to wild in the "Woahhh that run in the bike park was wild, dude!" sense of the word. I'm also not talking about the area's cowboy-associated reputation as the wild west. I'm referring to the abundant wildlife we're lucky to share our home with.

Outside The Gate

With a wrap on one of the snowiest years on record, many would surmise the ski season is over. But for those enlightened few, we know that is entirely untrue. The Aerial Tram opened for summer operations May 20th, and brings with it the return of the spring ski season for those adventurous few.

Waffles at Corbet's Cabin

Bring your crew to enjoy the delicious tradition of eating Top of the World Waffles atop Rendezvous Peak. There is no better place to enjoy a waffle than situated in Corbet's Cabin at 10,450 feet (accessed via the tram). And these aren't just any waffles — these are made to order with delicious toppings like brown sugar butter, nutella, peanut butter, bacon (yes, you read that correctly) and more.

Hiking

There are many amazing hikes in Jackson Hole, and a great deal of them are accessed via the tram. Relax as the tram elevates you 4500 feet directly into the incredible hiking areas in the national forest and Grand Teton National Park.

Tram Accessed Hiking

- Rock Springs Loop

- Corbet's Trail

- Cody Bowl

- Happy Hour Hike

Paragliding

Craving even more fresh mountain air? Let the professional tandem pilots at Jackson Hole Paragliding elevate your adventure. After a few running steps, you’ll soar high above Jackson Hole and the Teton and Snake River mountain ranges. Relax and inhale breathtaking vistas underneath your bright canopy in the sky.

Views from the Top

Gondolas

Your summer sightseeing ticket also grants you access to the Bridger Gondola and Sweetwater Gondola from June 6 - Sept 12, 2026. Sweeping views and a launch point for so many adventures await at the top, including premier hiking trails, yoga, paragliding and Via Ferrata tours. Grab a bite at one of our three different restaurants, including The Deck.

Tickets used between May 16 - June 5 and September 13 - October 4 grant one-day access to the Aerial Tram only.

Wildlife

The stunning geography of the rugged alpine environment may not be the only thing you observe while sightseeing. It's not uncommon to get a unique overhead view of moose, bears, or other amazing animals from the safety and comfort of the Aerial Tram and gondolas.

Backcountry Skiing

Guests are allowed to ski in the backcountry accessible through our boundary gates located near the top of the Aerial Tram, but as part of JHMR’s special use permit with Bridger Teton National Forest, no skiing is permitted within the ski area boundary after the winter operating season. Guests with ski gear will be allowed to load the Tram, but not the gondolas. Skiing and snowboarding are prohibited inbounds during the spring and summer seasons Hazards are not marked, construction efforts are underway, operational vehicles are on-mountain and ski patrol is not available for response.

Already bought your sightseeing ticket?

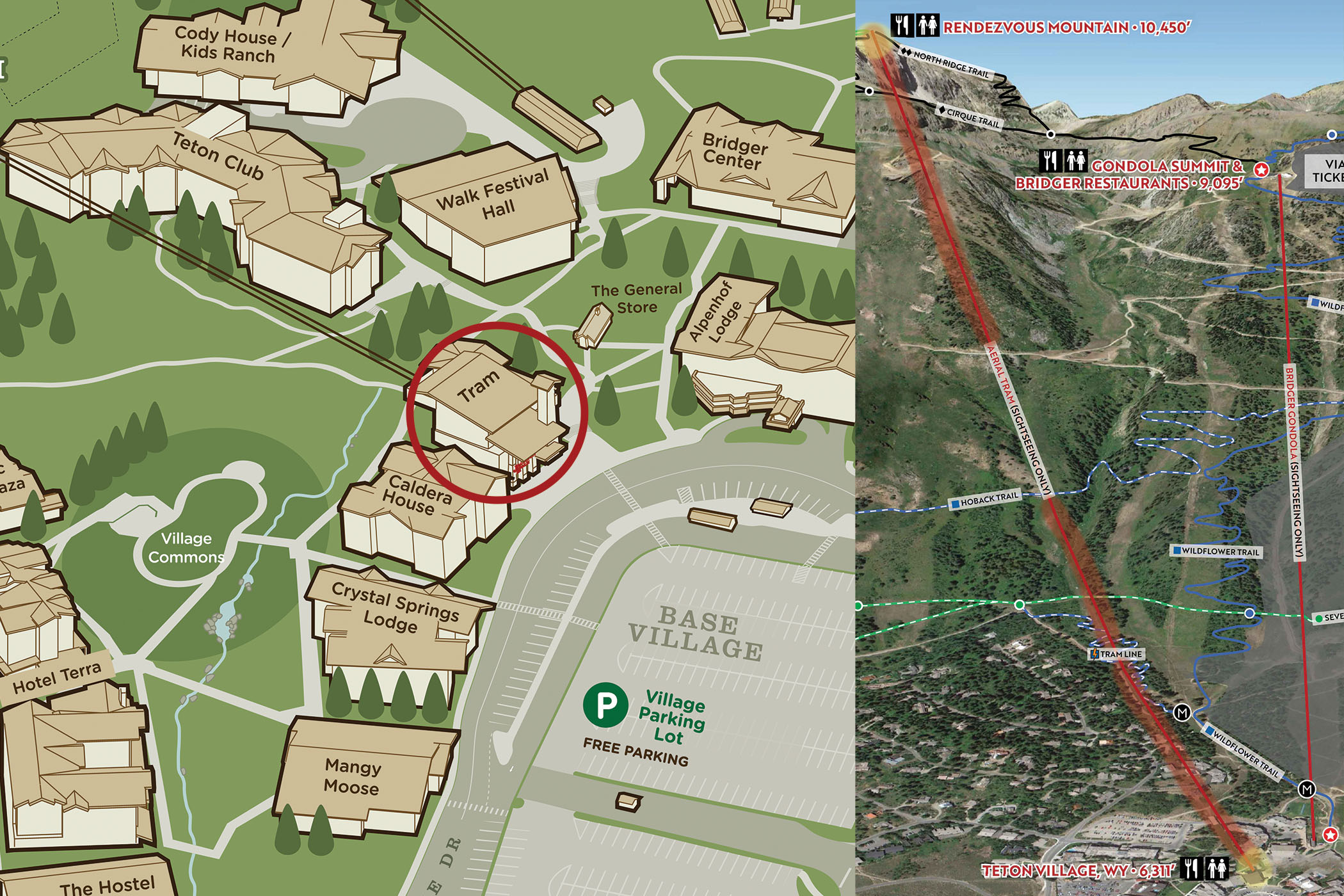

Explore everything that is included with your purchase and check out the base area map to navigate around Teton Village.

Includes Evening Gondola

Your sightseeing ticket includes a free evening gondola ticket.

Evening Bridger Gondola rides are the best way to end your lively day at the mountain. Offering unparalleled views and the best spot to take in an alluring sunset vista while you cap off your day with food and drinks on The Deck.

Please note: the complimentary evening gondola ticket must be used on the same day as your sightseeing trip.

2-for-1 Drink Specials

Included in your purchase

Off-Piste (The Deck)

5 PM - 8 PM

Enjoy 2-for-1 specials on draft beer, wine, coffee and hot cocoa.

Details

- One time use

- Excludes canned and bottled drinks, cocktails and sloshies

- Only available when The Deck is open (closed select dates)

Dog Policy

Summer Policy: During the summer season, service animals are permitted to both upload and download the Tram and gondolas. Non-service animal dogs are allowed to download the gondolas only; they are not permitted on the Tram and cannot upload via either transportation option.

Winter Policy: Throughout the winter season, dogs are prohibited from riding any chairlift, gondola, or Tram, regardless of whether they are service animals or not.

Adaptive Approved

We offer a variety of activities that bring the ultimate mountain experience to individuals of all ages and disabilities and/or adaptive needs.